Why did people think cannibalism was good for their health? The answer offers a glimpse into the zaniest crannies of European history, at a time when Europeans were obsessed with Egyptian mummies.

Driven first by the belief that ground-up and tinctured human remains could cure anything from bubonic plague to a headache, and then by the macabre ideas Victorian people had about after-dinner entertainment, the bandaged corpses of ancient Egyptians were the subject of fascination from the Middle Ages to the 19th century.

Mummy mania

Faith that mummies could cure illness drove people for centuries to ingest something that tasted awful.

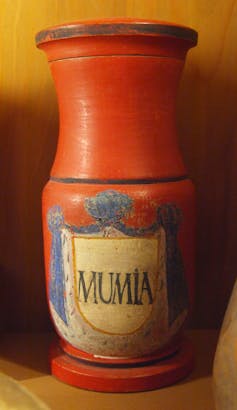

Mumia, the product created from mummified bodies, was a medicinal substance consumed for centuries by rich and poor, available in apothecaries’ shops, and created from the remains of mummies brought from Egyptian tombs back to Europe.

By the 12th century apothecaries were using ground up mummies for their otherworldly medicinal properties. Mummies were a prescribed medicine for the next 500 years.

In a world without antibiotics, physicians prescribed ground up skulls, bones and flesh to treat illnesses from headaches to reducing swelling or curing the plague.

Not everyone was convinced. Guy de la Fontaine, a royal doctor, doubted mumia was a useful medicine and saw forged mummies made from dead peasants in Alexandria in 1564. He realised people could be conned. They were not always consuming genuine ancient mummies.

But the forgeries illustrate an important point: there was constant demand for dead flesh to be used in medicine and the supply of real Egyptian mummies could not meet this.

Apothecaries and herbalists were still dispensing mummy medicines into the 18th century.

Mummy’s medicine

Not all doctors thought dry, old mummies made the best medicine. Some doctors believed that fresh meat and blood had a vitality the long-dead lacked.

The claim that fresh was best convinced even the noblest of nobles. England’s King Charles II took medication made from human skulls after suffering a seizure, and, until 1909, physicians commonly used human skulls to treat neurological conditions.

For the royal and social elite, eating mummies seemed a royally appropriate medicine , as doctors claimed mumia was made from pharaohs. Royalty ate royalty.

Dinner, drinks, and a show

By the 19th century, people were no longer consuming mummies to cure illness but Victorians were hosting “unwrapping parties” where Egyptian corpses would be unwrapped for entertainment at private parties.

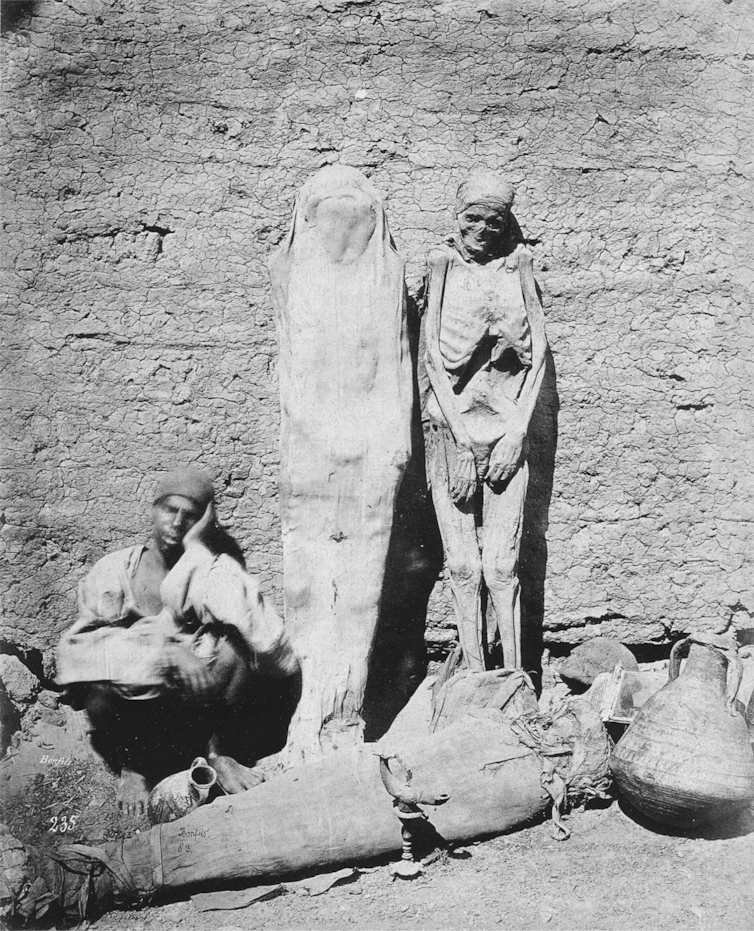

Napoleon’s first expedition into Egypt in 1798 piqued European curiosity and allowed 19th century travellers to Egypt to bring whole mummies back to Europe bought off the street in Egypt.

Victorians held private parties dedicated to unwrapping the remains of ancient Egyptian mummies.

Early unwrapping events had at least a veneer of medical respectability. In 1834 the surgeon Thomas Pettigrew unwrapped a mummy at the Royal College of Surgeons. In his time, autopsies and operations took place in public and this unwrapping was just another public medical event.

Soon, even the pretence of medical research was lost. By now mummies were no longer medicinal but thrilling. A dinner host who could entertain an audience while unwrapping was rich enough to own an actual mummy.

The thrill of seeing dried flesh and bones appearing as bandages came off meant people flocked to these unwrappings, whether in a private home or the theatre of a learned society. Strong drink meantaudiences were loud and appreciative.

The mummy’s curse

Mummy unwrapping parties ended as the 20th century began. The macabre thrills seemed in bad taste and the inevitable destruction of archaeological remains seemed regrettable.

Then the discovery of Tutankhamen’s tomb fuelled a craze that shaped art deco design in everything from the motifs of doors in the Chrysler Building to the shape of clocks designed by Cartier. The sudden death in 1923 of Lord Carnarvon, sponsor of the Tutankhamen expedition, was from natural causes but soon attributed to a new superstition – “the mummy’s curse”.

Modern mummies

In 2016 Egyptologist John J. Johnston hosted the first public unwrapping of a mummy since 1908. Part art, part science, and part show, Johnston created a an immersive recreation of what it was like to be present at a Victorian unwrapping.

It was as tasteless as possible, with everything from the Bangles’ Walk Like an Egyptian playing on loud speaker to the plying of attendees with straight gin.

The mummy was only an actor wrapped in bandages but the event was a heady sensory mix. The fact it took place at St Bart’s Hospital in London was a modern reminder that mummies cross many realms of experience from the medical to the macabre.

Today, the black market of antiquity smuggling – including mummies – is worth about US$3 billion.

No serious archaeologist would unwrap a mummy and no physician suggest eating one. But the lure of the mummy remains strong. They are still for sale, still exploited, and still a commodity.